Open space, parks, green spaces, natural areas – including wetlands, riparian corridors, farmland, beaches, rivers, lakes, the ocean, fields and forests – provide demonstrable mental and physical health benefits. They have proven to be preventative measures that can actually lower health care costs and reduce the need for health interventions. Exploring or even just gazing upon natural areas – such as a swamp or mangrove-fringed estuary next to a city – gives human beings a sense of perspective, continuity in a changing world, spiritual renewal, well-being, and a feeling of harmony with the world around us. The presence of open space within and adjacent to our urban areas – and the assurance that this open space will outlast us – serves to counterbalance the stress and strain of modern life.

Contact with nature and open space provides both physiological and psychological benefits. Research on the physiological benefits of open space has centered on how direct or indirect (vicarious) experience with vegetated and/or natural landscapes reduces stress, and anxiety.

A series of studies spanning nearly 20 years in the seventies and eighties linked photo simulations of natural settings to reduced stress levels as measured by heart rate and brain waves. One study revealed that subjects experienced more “wakeful relaxation” in response to slides showing vegetation only and vegetation with water compared to urban scenes without vegetation. These data were corroborated by attitude measures which indicated lower levels of fear and sadness when experimental subjects observed nature-related slides, as opposed to urban slides. In studies of hospital patients, recovery was faster, there were fewer negative evaluations in patient reports, and there was less use of anesthetic medication among post-surgery patients with views of exterior greenery than among control group patients with views of buildings (Views through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224, 420-421).

Central Park Has Been Called a “Green Oasis” in New York City

In other research, breast cancer survivors who engaged in personally enjoyable and nature-related “restorative activities” showed dramatic effects on their cognitive process and quality of life. At the end of three months, the experimental group showed significant improvements in attention and self-reported quality of life measures; they had begun a variety of new projects. Control group members, meanwhile, who had been given no advice regarding nature exposure activities, continued with deficits in measures of attention, had started no new projects, and had lower scores on quality of life measures. This research underscored that difference between nature as an amenity and as a human need. As one reviewer of the study observed:

“People often say that they like nature; yet they often fail to recognize that they need it…Nature is not merely ‘nice.’ It is not just a matter of improving one’s mood, rather it is a vital ingredient in healthy human functioning.”

There is an important distinction between nature as amenity and nature as need. As one book affirms:

“Viewed as an amenity, nature may be readily replaced by some greater technological achievement. Viewed as an essential bond between human and other living things, the natural environment has no substitutes.”

While there are many anecdotal reports linking the natural environment or open space to everything from increased self-esteem to stress reduction, there are few studies attempting to categorize the many phrases used to identify the worth of a walk in the woods or a day bird-watching beside a marsh. Few studies track long-term longitudinal effects on changed attitudes and behavior. While it is difficult to characterize and quantify the long-term, intangible manner in which lives are modified, it is easy to acquire narrative accounts about the effect of a favorite overlook, trail, or patch of woods on one’s psyche. One of the best known of such testimonials is from pioneering naturalist-conservationist John Muir:

“Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop away from you like the leaves of Autumn.”

Natural settings are unparalleled in their ability to furnish solitude, privacy, and tranquility. They also have “existence value,” that is, there is value to knowing that they are simply there and to the very idea that we could get away into them, if we so chose; this is a value in and of itself, which provides for a psychological “time-out” and a sense of wellbeing.

Most Americans recognize the value of nature and open space for their emotional well-being.

Almost 90 percent say it is “very” or “somewhat” important that they be able to easily access Natural Areas and Open Space.

A May 2020 survey of 1,500 likely American voters of 1,500 likely American voters addressed this connection directly:

73% Yes

16% No

11% Not sure

45% Very important

40% Somewhat important

10% Not very important

2% Not important at all

3% Not sure

Almost three-quarters said they feel an “emotional or spiritual uplift” from time spent in natural areas, while 85 percent indicated that it is important to be able to reach natural areas “fairly quickly” from their homes. These findings are similar to those of another public opinion poll conducted of more than 1,000 likely Colorado voters in June 2022.

63% very important

26% somewhat important

7% not very important

2% not at all important

2% not sure

The lead author of this study (Kolankiewicz) is an avid hiker and has frequently been surprised at the number of Americans who share his pastime or passion, such as the hundreds of hikers he encountered on one hot weekday evening in an ascent of Piestewa Peak in Phoenix, AZ and hundreds more on a typical autumn Saturday afternoon on the edge of Boulder, CO embarking on a hike to the Flatirons, a prominent landmark on the Colorado Rocky Mountain Front Range.

Hikers on popular Piestewa Peak in the Phoenix-Mesa Urbanized Area

View of the Flatirons in the Colorado Front Range near Boulder

While not garnering the media attention it once did, the topic of urban sprawl remains a major concern to many American citizens.

According to the Land Trust Alliance, voters still care deeply about conserving our remaining natural land, approving over 80% of land conservation measures on the ballot around the country in November 2012. The 46 measures passed nationally in 2012 provided a total of $767 million to protect and improve water quality, acquire new parks and open space, and conserve working farms and ranches. Many of the referenda won by landslides – 27 measures passed with at least 65% of the vote.

National and regional non-governmental land conservancies such as The Nature Conservancy, the Trust for Public Land, the North Florida Land Trust, the New Mexico Land Trust, and the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy continue to garner substantial public support. In the November 2016 election alone, 25 land conservation ballot measures were voted on in 10 different states.

In 2018, the Trust for Public Land helped communities draft and campaign for 18 ballot measures on Election Day 2018. Voters approved all but one of the 18. In total, of some 61 ballot measures vote on nationwide in 2018, 52 passed, including two in Arizona. By a margin of 56 to 44 percent, Tucson voters approved $24 million in bonds for parks and recreation (parks, trails, recreation, greenways), while voters in Mesa approved $5.9 million for parks and recreation by the same margin. Nationwide, on Election Day in 2019, voters approved 33 of 41 ballot measures, raising over $900 million in funding for conservation. Overall, between 1988 and 2019, American voters passed 2,096 of 2,758 the open space ballot measures (76 percent) they voted on.

While these were not anti-sprawl measures per se, they do indicate that the American public cares deeply about preserving open space, and is willing to “put its money where its mouth is.”

Urban sprawl imposes significant economic and financial costs on the public. These costs are often hidden in the form of taxpayer subsidies to build new roads, water supply systems, sewage collection and treatment systems, and schools to accommodate runaway growth.

In short, Americans still value our rural lands and natural habitats; oppose heavy traffic, gridlock, and longer commute times to work and to daily, weekly, and monthly open-space destinations; and dislike increased environmental degradation, greater economic costs, and higher taxes; all of which are part of the price tag of sprawling urban development.

Polling shows that sizeable majorities of Americans feel strongly about the need to protect farmland and natural habitats for themselves, for their fellow Americans, for posterity, and for the nation’s wildlife (see “From Sea to Sprawling Sea,” Appendix G). Large majorities also indicate it is important to have ready access to natural areas and open space and that they feel spiritually and emotionally rejuvenated by the time they spend in natural areas.

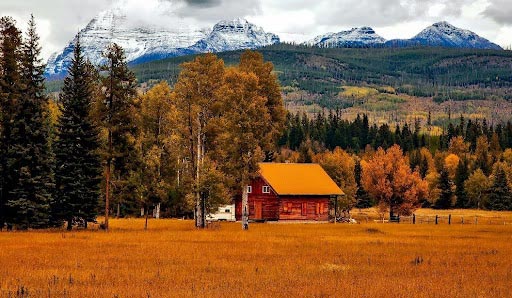

Picturesque Colorado countryside