A biome is a floristic region, that is, a large, naturally-occurring community of flora and fauna consisting of a dominant habitat, e.g., forest, grassland, or desert. The United States boasts a number of diverse biomes that reflect its varied climates and geology.

Within the biomes and landscapes threatened by sprawl are found some of our most critical natural habitats. According to the World Wildlife Fund, habitat loss poses the single greatest threat to endangered species around the world. The United States is home to approximately 1,660 species and sub-species of plants and animals formally listed as federally endangered or threatened by the federal government (specifically, by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service). Most of these are seriously harmed by ever-expanding sprawl and ever-encroaching development of one form or another that modifies, degrades, or eliminates the habitats they need to survive.

Biomes of North America

Source: Virginia Tech Dendrology Factsheets

Endangered species, sub-species, or populations are those rare plants or animals that, if recent trends continue, will likely become extinct within the foreseeable future, barring heroic measures to save them. Threatened species or sub-species may become endangered within the foreseeable future. American habitats support flora and fauna, some of which have become imperiled in the state (in danger of “extirpation” or elimination over part of their overall range) but enjoy healthy populations elsewhere in their range, and others of which are threatened or endangered over large parts of their overall range, throughout their entire U.S. range, or are imperiled on a global scale (that is, they have no healthy populations anywhere).

Habitat loss imperils wildlife much more than other factors such as pollution, toxics, invasive species, road mortality, overhunting, or poaching.

A 2019 study by scientists with Conservation Science Partners for the Center for American Progress identified urban, agricultural, energy, and transportation “stressors” as the major causes in the loss and fragmentation of natural habitat in the lower 48 states. Population growth exacerbates each of these factors.

For example, more people need more farmland to cultivate the crops that become the food that feed those additional numbers. More people require more aggregate energy production to meet more aggregate consumption, hence more land is needed for petroleum exploration and development, access roads, pipelines, coal mines, wind farms, solar arrays, and so forth.

The Conservation Science Partners study concluded that expansion and intensification of land uses in the U.S. resulted in a steady, inexorable loss of natural areas between 2001 and 2017. In these 16 years alone, more than 24 million acres of natural lands and habitats were permanently modified or lost to development, at an average of 1.5 million acres per year. Just how enormous this loss is can be understood by comparing it to the areas of some of America’s largest, most beloved national parks, our “crown jewels.” The natural habitats lost in just 16 years were equivalent in size to almost nine Grand Canyon National Parks, more than 10 Yellowstone NPs, or 49 Great Smoky Mountains NPs.

The urban stressor accounted for 57 percent of all the natural lands lost during the 16-year study period. Thus, urban sprawl devours more natural habitat than all other major causes of habitat loss combined.

Let’s look briefly at three habitat types and wild creatures associated with them that long-term population growth, sprawl, and development have drastically impacted over the years. These are not the only imperiled habitats, but they are representative of what is at stake.

Longleaf Pine Ecosystem – The once widespread but now severely diminished longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) ecosystem once dominated as much as 90 million acres from southern Virginia to Florida and west to eastern Texas. It was once one of the largest ecosystems in North America. Now it occupies less than five percent of its former range. The longleaf pine ecosystem contains possibly the most species-rich communities outside of the tropics, including many highly endangered species such as the Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis). Agriculture (to feed growing a growing human population), timber harvest, inappropriate fire management (excessive suppression), and urbanization have all taken a toll on the longleaf pine ecosystem.

Longleaf Pine Ecosystem in the Southeast – More than 95% of it has been lost to Agriculture, Logging, Fire Suppression Practices, and Development

Red-cockaded Woodpecker

Tallgrass Prairie Ecosystem – Prairies once covered 170 million acres in North America. This legendary “sea of grass” reached all the way from the Rocky Mountains to east of the Mississippi River and from Saskatchewan, Canada, in the north to Texas in the south. The tallgrass and shortgrass prairies supported an unfathomable quantity of living tissue or biomass – plants and animals galore – including the iconic, immense, thundering bison herds (some 30-60 million strong), upon which both the Plains Indians and the now-extinct Plains Grizzly and many other living things depended.

The historic, unplowed tallgrass prairie ecosystem exemplified the ancient, complex web of life and the ecological food pyramid. As an observer gazed upon the undulating waves of grass, at first it would have appeared as if the entire prairie landscape consisted only of grasses, some 40 to 60 species of which did indeed comprise about 80 percent of the extant flora. The other 20 percent of the plants consisted of more than 300 species of forbs or flowers, as well as over 100 species of lichens and liverworts. Many varieties of shrubs and trees flourished in riparian zones in the moist soils along creeks. The rich, productive plant community in turn supported grazing animals in great numbers, such as elk, deer, and antelope, in addition to the bison. Smaller wildlife such as songbirds, hawks, mice, and gophers abounded. Grizzly bears and wolf packs preyed upon the grazers. Plants fed the herbivores, and herbivores fed the carnivores and omnivores, whose nutrients were returned to the soils and recycled by the decomposers, in the great “Circle of Life.”

Euro-American settlers discovered the fertile prairie soils about 150 years ago in their march westward across the continent. Learning that these rich, thick topsoils – chockfull of nutrients that had accumulated for millennia – excelled at growing crops and yielding bumper harvests, the settlers plowed the prairie virtually everywhere. Wheat and corn for a rapidly growing, hungry nation were the primary or staple grain crops, but many others were cultivated as well. At present, the most fertile and well-watered part of these once-vast grasslands, the tallgrass prairie, has been reduced to a mere one percent of its original expanse. The once-vast tallgrass prairie is now considered one of the rarest and most imperiled ecosystems on Earth. The largest remaining area of tallgrass prairie never plowed is in the stony, hilly region of Kansas known as the Flint Hills, southeast of Wichita.

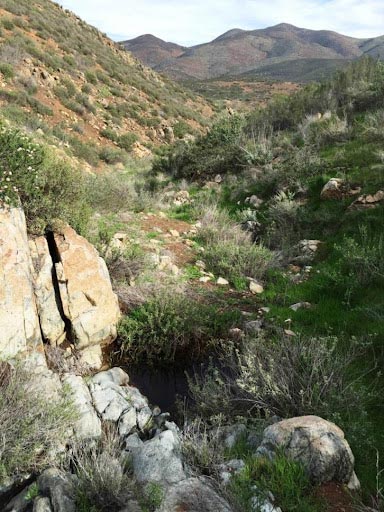

Coastal Sage Scrub Ecosystem – The aromatic coastal sage scrub ecosystem extends from the San Francisco Bay region southward along California’s coast to the Mexican border and beyond. It is characterized by such plant species as white, black and purple sage, California sagebrush, buckwheat, bush sunflower, laurel sumac, and lemonade berry. It is home to bobcats, ground squirrels, lizards, rattlesnakes, ravens, turkey vultures, and roadrunners, among other creatures. It also provides refuge for the threatened California gnatcatcher

(Polioptila californica californica).

Coastal Sage Scrub on the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge

The gnatcatcher is a tiny, blue-gray songbird in the old-world warbler and Sylviidae family. It is less than five inches long and weighs just six grams. In spite of its petite size, this feisty bird is known to mob much larger birds that are potential nest predators, such as the California scrub-jay, cactus wren, and roadrunner. Mobbing these larger birds bothers them and drives them away from vulnerable nestlings.

Adult male California gnatcatcher in its summer breeding plumage

The California gnatcatcher feeds mainly on small insects and spiders, including beetles, caterpillars, wasps, ants, flies, moths, small grasshoppers, and of course, gnats. It may also eat small berries. One of its adaptations to a semi-arid environment with few perennial surface streams is cleaning its feathers by using water deposited on leaves by rain or coastal fog. The gnatcatcher survives in just six counties in Southern California and a tiny bit of Mexico. It is entirely dependent on coastal sage scrub habitat, an estimated 60-90 percent of which has disappeared under the infamously sprawling suburbs, subdivisions, and freeways of Southern California. Massive post-World War II population growth is the main driver of this sprawl.